In an ideal, 100 per cent efficient internal combustion engine, the fuel would burn to give just carbon dioxide and water vapour. In practice, of course, engines are far from efficient and the combustion process. also produces carbon monoxide, oxides of nitrogen and unburnt hydrocarbons, as well as carbon dioxide and water vapour.

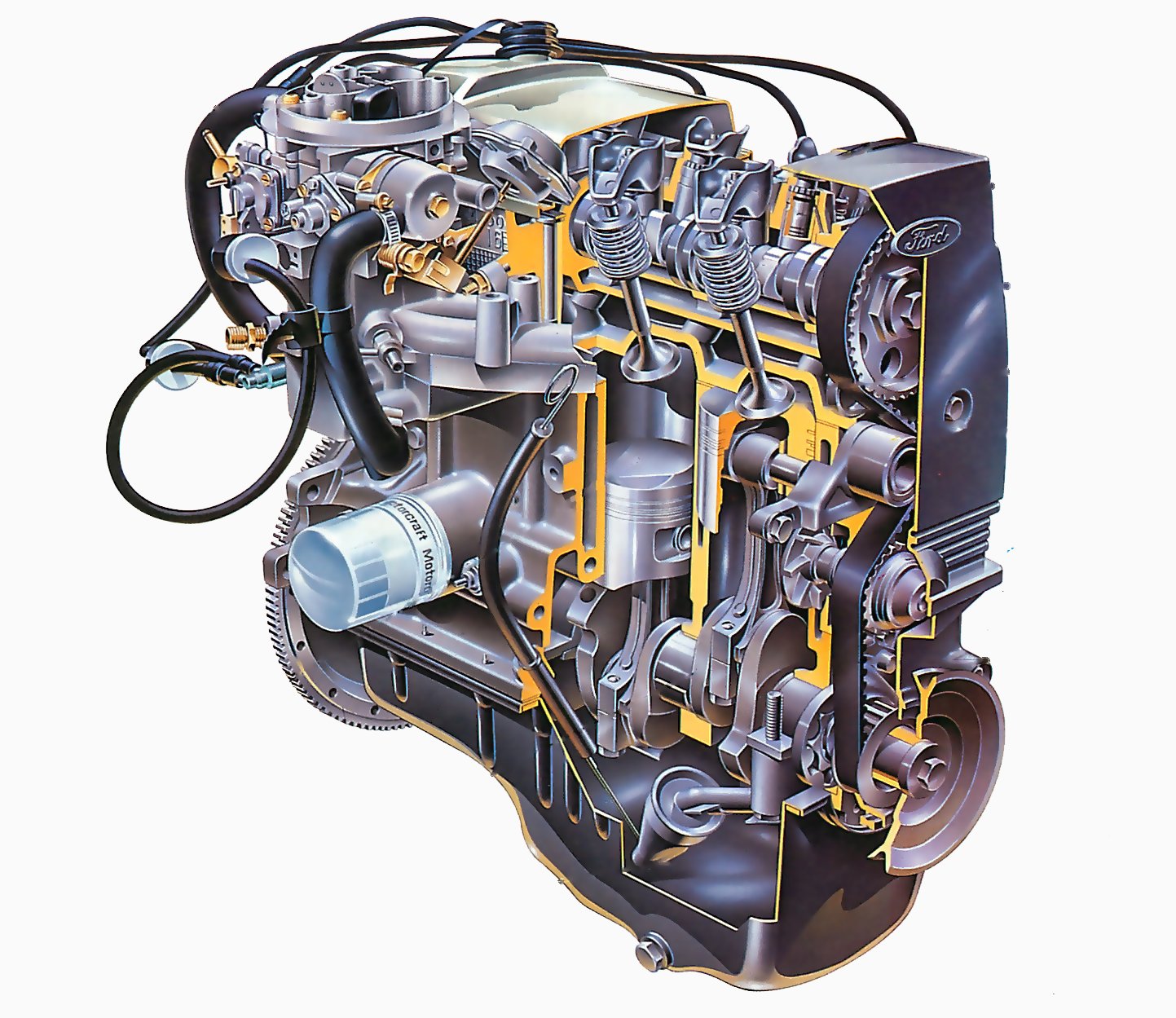

Ford CVH Lean-burn engine

In 1980 Ford introduced their CVH engine in the Escort 3, as a replacement for the old five-bearing pushrod OHV Kent engine. The engine's designation derives from its design — Compound Valve angle, Hemispherical combustion chamber.

Now the CVH has been re-engineered to make it a true lean-burn engine, capable of running on air-fuel ratios of over 18:1. This meant a change in the cylinder head design to incorporate a lean-burn kidney-shaped combustion chamber to ensure high mixture swirl and therefore more complete fuel burning.

These by-products of combustion are expelled as part of the car's exhaust gases into the atmosphere where they cause pollution.

In recent years, public concern about atmospheric pollution, and imminent EEC pollution-control laws, has led to car manufacturers trying to find ways of reducing the level of these gases in car exhausts.

This video course is the best way to learn everything about cars.

Three hours of instruction available right now, and many more hours in production.

- 4K HD with full subtitles

- Complete disassembly of a sports car

Approaches

There are two basic approaches to reducing harmful exhaust emissions - using lean-burn engines or attaching catalytic converters to the exhaust system.

Lean-burn engines are designed to produce a lower level of harmful emissions by better combustion control and more complete burning inside the engine cylinders.

Catalytic converters clean up the exhaust gases coming from the engine. Catalysts are the older of the two systems, and have been used in the US and Japan for some years.

Catalysts

Catalytic converters are fitted by the car manufacturer downstream of the engine in the exhaust system. It looks like a slightly swollen silencer and contains a fine metal or ceramic honeycomb, coated with platinum or a related metal, across which the exhaust gases flow.

The platinum initiates a chemical reaction in which the harmful exhaust constituents are converted into harmless nitrogen, carbon dioxide and water vapour.

The problem with catalytic converters is that they sap engine power and reduce fuel economy. They also lead to increased maintenance costs.

Another drawback is that the catalytic system needs unleaded petrol to work properly, because any lead in the exhaust gases quickly ruins the catalyst's efficiency. And some European countries, such as Britain, have none or very few outlets for unleaded petrol, with little hope of establishing a comprehensive network for distributing the new fuel in the near future.

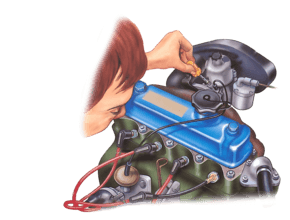

Inside the CVH combustion chamber

Ford's lean-burn engine, based on the CVH, has a combustion chamber which is kidney shaped — it looks rather like an off-centre hemispherical chamber.

This type of design ensures good breathing, and the enhanced 'squish' effect means that the fuel and air will be well mixed for ignition. The mixture is forced up and sideways into the kidney shape of the chamber, rather than just being pushed into the more regular hemisphere of the earlier design.

With the piston on its downward stroke, the inlet valve opens to let in a charge of fuel and air. As the mixture enters the cylinder, it 'swirls'.

The piston begins its upward stroke to compress the mixture. In doing so, it mixes the fuel and air fully by squashing it into the combustion

The spark plug fires and ignites the mixture inside the combustion chamber. The flame begins to travel quickly through the chamber.

The efficient fuel/air mixing allows the flame to continue travelling evenly through the combustion chamber and drive the piston down.

Leaner mixtures

These problems have forced car manufacturers to look elsewhere for ways of reducing exhaust emissions. The most obvious avenue for reducing emissions is to burn less fuel in the first place.

This requires an improvement in thermal efficiency, which is now very difficult to achieve because all the readily available routes have already been implemented.

One remaining possibility is to produce a 'leaner' mixture, namely to reduce the proportion of fuel in the fuel/air mixture entering the engine.

Fuel/air ratios

Petrol burns best in a standard car engine when it is mixed with air in the proportions 14.7:1 - nearly 15 parts of air to every one part of petrol. In practice the mixture strength varies between about 13:1 and 16:1, depending on the speed of an engine and its load at the time. At these mixtures, engines produce fairly high levels of harmful exhaust gas emissions, particularly during initial acceleration.

When you try to move away from the ideal fuel/air ratio, the engine's running is affected - if the engine is fed too much fuel it produces smoke, wears out quickly and is expensive to run. If the engine is made to run too lean, combustion becomes extremely variable from one cycle to the next, exhaust gas temperatures rise because of the persistence of flames from 'late-burn' cycles, and the engine starts to misfire frequently. All of these result in high levels of hydrocarbons in the exhaust gases.

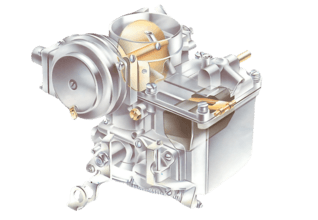

To overcome the difficulties in making an engine run well on leaner mixtures, the air/fuel mixture needs to be more intimately mixed and the actual spark timing and combustion process needs to be very finely controlled.

Engine management

To this end, some car manufacturers are fitting engine management systems where sophisticated electronics control both the ignition and the fuel delivery systems. This makes it possible to make sure that the spark plugs fire at just the right moment to ignite a fresh fuel/air charge, which may otherwise be reluctant to ignite.

Also under development are engine parts made of new materials that have greater heat resistance, such as pistons made of ceramics. But most development is going into ensuring that the air and fuel are well mixed.

Stir the mixture

In reducing the proportion of fuel in the mixture entering the engine, car manufacturers have encountered problems with misfiring and incomplete combustion which have, in some cases, increased rather than decreased fuel consumption.

To get round these problems, the industry has tried different ways of `stirring' the mixture just prior to ignition, with the aim of promoting faster burning and more complete combustion.

There are three main ways of stirring the mixture. First, the engine's inlet ports can be shaped to cause swirl - a technique borrowed from direct injection diesel engines. Second, a deflector, or 'fence', around which the mixture has to flow, may be positioned near the inlet valve or valves. And third, the combustion chamber itself can be made smaller than the cylinder bore to create what is known as a 'squish' effect - under compression from the upcoming piston, the fuel / air mixture has to squeeze itself into the combustion chamber, and this increases the density of the fuel droplets in the chamber.

Working out how best to design the engine so it can cope with very lean fuel mixtures is a very difficult process. Part of the problem is trying to see what actually goes on inside a combustion chamber when the fuel/air mixture is burning, particularly when the throttle is rapidly opened or closed.

So researchers are now using a quartz window in the combustion chamber, combined with a cine camera and complex computer programming, to see exactly what is going on inside. From this they can tell how and where the flame is spreading, which gives an indication of how fully the mixture is burning.

The way ahead

Toyota's partial lean-burn system

The latest Toyota engine, featuring turbocharging and supercharging and used in their FXV concept car, has the inlet ports for each cylinder separated into two — one straight and one helical. At high engine speeds, both ports are open, but at low loads, a control valve in the straight port remains closed. All the mixture goes down the helical port, creating a swirl effect in the combustion chamber. This swirl mixes the fuel and air more fully. The fuel content in the mixture is very finely metered by individually controlled injectors to increase clean running still further.

The current generation of lean-burn engines run on ratios of around 17:1 or 18:1, and the next generation should run with ratios averaging 20:1 or 22:1.

But lean-bum technology still has some way to go before it fully meets the proposed EEC laws. Some manufacturers are proposing to use a combination of a catalyst and a lean-burn engine to meet the demands of the new regulations.

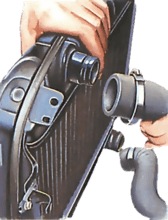

Turbulence Grid

A British company, Epicam, is developing a turbulence grid to help control the motion of the fuel/air mixture before it enters the engine.

The grid is mounted on the upper surface of the inlet valve, creating high-speed microturbulence in the mixture as it enters the combustion chamber. The grid's microturbulence has advantages over the eddies (turbulence) in current lean-burn engines. Large eddies can cause problems in initial ignition and later in the engine's cycle, when the ignited mixture can lose heat via a 'scrubbing' effect on the cylinder walls, or even extinguish itself.

A problem with the turbulence grid is that it can impede the airflow into the engine, which reduces the power, but with careful design this can be kept to minimum.